Where does mass come from?

Posted on Wed 18 March 2020 in Physics

I’m a bit over halfway through a brilliant set of particle physics lectures by Don Lincoln, called The Theory of Everything: The Quest to Explain All Reality. Don has spent many years as an experimental particle physicist, and has worked with particle accelerators at both at Fermilab and at CERN. You may remember him from his co-discovery of the top quark in 1995, or from his membership on the CERN team when they discovered the Higgs boson in 2012. Or heck you might have seen one of his TED talks. Either way you have this set of lectures, Don Lincoln, and Don’s moustache to thank for today’s episode.

This fascinating (to me) lecture series takes us on a journey through the four known forces of the universe – the strong nuclear force, the weak nuclear force, the electromagnetic force, and the gravitational force. I’ve spent literally hundreds of hours reading on this esoterica (glares pre-emptively at autocorrect), and I know it’s a baffling area, so I’m really just going to skirt around the edges of this. But one particularly outstanding part really got my interest, and I think I can write it in an understandable form here. Wish me luck… ☘️

This post is on the topic of mass. To start looking at this we go down to the foundations of matter – let’s take a quick journey through mass:

What are things?

To get us started, I’ve put the below into a bulleted list – every level is the next step down in matter:

-

You, a standard human being, are made up of molecules (mostly water), along with a collection of bad ideas and faulty memories. I’m not judging.

-

Those molecules in your body are made up of atoms – mostly carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen.

Let’s look closer at hydrogen. *squints*-

A hydrogen atom is the simplest atom. It has the atomic number of 1, meaning its nucleus has only a single proton, which is balanced by a single electron.

Side-note: Hydrogen is a little special because it doesn’t have a neutron in its nucleus. In contrast, heavy hydrogen – known as deuterium – has a proton, an electron, and a neutron.

-

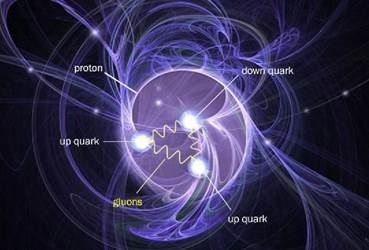

A proton is, in turn, made up of three quarks, and weighs roughly 938 MeV/c2. (that’s megaelectronvolts… more below)

-

An up quark (carrying a positive electric charge of “plus two-thirds”) has a mass of roughly 2.3 MeV/c2 (ignore that part)

-

The down quark (carrying a negative electric charge of “minus one-third”) has a mass of roughly 4.8 MeV/c2 (ignore that too, the fun bit is coming)

-

(Quarks appear to be made up of strings, but that’s too deep for this article. Extra credit: String theory, superstring theory, and M theory)

-

Holding the quarks together are the Gluons, which are the particles which mediate the strong nuclear force. These are massless-ish, coming in at almost exactly 0 MeV/c2.

-

-

A proton is made of two up quarks and a down quark, which gives it a total electric charge of +1. (four-thirds from the up quarks, minus a third from down quark)

-

-

The electron is not made up of quarks – it appears to be a primary particle (specifically, a lepton) that cannot be subdivided. It has an electric charge of -1, and a mass of about 0.5 MeV/c2.

-

-

-

What’s a MeV, and has it been approved by the FDA?

Okay, so you’ve probably never seen mass described in MeV/c2 before. That’s because people live in the world of Relatively Big Things™, so we generally think of mass as what you might measure on a set of bathroom scales (also known as m’ass). But when you’re looking at particle physics, things get way fuzzier... SO fuzzy, in fact, that we don’t weigh things in grams – we weigh them in energy! Specifically, in electron-volts.

For example, a proton weighs 938 million electron-volts (/c2), and an electron weighs about 500,000 electron-volts. CBut… how does *that* work? How on earth do we measure mass in energy? You wouldn’t say "this glass weighs 500 calories", would you?

HECK YEAH, you would! It’s the formula most deeply burned into your brain from high school: E=mc2. Energy (in joules) = Mass (in kilograms) * the speed of light (in metres per second) squared. Einstein’s been saying it for over a hundred years… mass is energy, and energy is mass! And mass contains a whole honkin' bunch of energy. So much energy that a single gram of matter – about the mass of a business card – looks something like this:

Energy (joules) = 1 gram * speed of light^2

Energy (joules) = 0.001 * 300000000 * 300000000

Energy of 1 gram of matter = 9,000,000,000,000,000 joules

... or about 2,151,051,625,239 calories.

So yep, you can definitely weigh things in energy ... and because subatomic particles are so small, energy is a totally sensible measure to use. So let’s get back to the world of the extra-tiny.

Those numbers look fishy...

Yes, those numbers are weird. And I’m not talking about my equations above, I’m talking about the mass of an atom. Check it out again:

Proton = 2x up quarks + 1x down quark = 938 MeV/c2

But the two up quarks only bring 4.6 MeV/c2 to the party, and that down quark is only 4.8 MeV/c2, adding up to a mere 9.4 MeV/c2. In fact, when you put together the mass of all the components of a proton, you still only see about 2% of the mass of the proton. So… where’s all that other mass coming from?

Well, okay. Those quarks aren’t just sitting stationary – they’re moving around at nearly the speed of light, within an incredibly tiny area. In fact, these quarks are fizzing around in an area approximately one-quadrillionth of a meter.

And here’s the whole idea that got me writing this post:

Our quarks, zooming around near the speed of light, and confined within such an incredibly tiny area… Well heck, that’s a whole lot of energy.

And what is energy?

It's mass.

And that is where most of the mass of an atom comes from. From this kinetic energy, found within in the quantum foam, and expressing itself in our universe as mass.

fin.